My Religious Deconstruction: Indoctrination Isn’t Funny

Indoctrination is psychologically abusive—even when unintentional. I've experienced its effects firsthand.

This is one of a series of posts titled “My Religious Deconstruction.”

This series aims to document the primary experiences, ideas, and choices that motivated me to question my Christian worldview—and renounce it.

Over two years ago, an old man at church said to me half-jokingly, “You have to indoctrinate kids when they’re young. That’s how you get converts.”

I felt sick—but said nothing. Instead, my mind became immediately reflective about when I was in Christian school. “Was I indoctrinated all those years?” And then I realized the soul-wrenching irony I was participating in: “I’m a youth leader at my church’s youth group. Am I the indoctrinator now?”

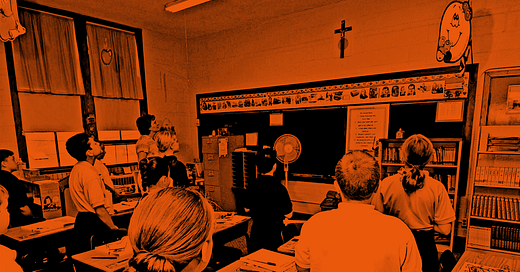

My life followed a pattern: weekly church services, Christian school, Christian summer camps, Christian sports teams, Christian events. My entire life was wrapped up in the Christian community and I had never really stepped outside of it. I was stuck in a bubble, helping it grow, participating in what I saw to be the brainwashing of the next generation, completing the sickening cycle.

Indoctrination is when individuals or groups of people condition someone (usually a child) into adopting certain ideas uncritically. It usually happens with children because their ability to think critically is not yet fully formed and they often don’t have the life experience or self-awareness to know that the well-intentioned person they think is taking care of them might be harming them. Additionally, adults can be indoctrinated so much themselves that they think they are doing the child a favor (as was the case with the old man).

There are essentially two main methods by which an indoctrinator can get a child to accept views: restriction of information and emotional manipulation. Both go hand in hand.

For example, in Christian Fundamentalist cults in America, information is tightly controlled. For example, some churches develop their own textbooks, courses, and other media containing false or misleading statements that fit with Christian dogma—some even going so far that they create their own media companies.1 Not only is information tightly controlled, taking seriously or enjoying “outside information”—such as the theory of evolution or a heavy metal song—is so frowned upon that many individuals feel emotionally compelled to avoid looking at or listening to such things because they would be criticized and possibly ostracized by their community. This, too, is a form of informational control—one that encourages the indoctrinated individual to restrict his own access to information. I’ve been put under informational control and I have experienced these feelings first handedly.

Although I technically could purchase curse-word laden music on my newly acquired iPod (thanks Steve Jobs), I felt reluctant to do so because I didn’t feel I should. My parents and Christian community told me that mainstream music was “this worldly” at the very least, and “of the devil” on the extreme. Even just two years ago, I felt an uncontrollable panic when Sam Smith’s Unholy started playing from my Spotify playlist while I was driving my Christian friends. (For those unfamiliar, Unholy drove parts of the Evangelical community into a 21st century “satanic panic” because Smith’s music video depicts “devilish elements” like all red clothing, a red top hat with devil horns, and erotic dancing.)

At the time, I was keeping it a secret from my Christian community that I was seriously doubting my faith and that it felt as if I was “sinning before them” by having this song on my playlist. I felt driven to lie about the song and say, “Oh, that’s weird. How’d that get on my playlist?” In reality, I enjoyed listening to this kind of song when I was alone because it gave me the rebellious outlet I needed after so many years of repressing my desire to explore these “sinful” songs.

This experience (and others) made me realize something: The fact I felt such a visceral reaction in the presence of my “friends” was an indicator that I was indoctrinated.

In the presence of my secular friends, I didn’t feel emotionally compelled to lie. And, with them, there were no moral implications or condemnation involved with listening to any kind of music—only enjoyment, or at the very least, consideration of the song’s merit before coming to a conclusion.2

This is only one instance of how indoctrination has harmed me mentally.

Now contrast indoctrination with teaching—a process that properly involves presenting facts and asking kids to only accept the ideas if they’ve critically examined them. This doesn’t lead to harm but independent minds.

With indoctrination, the adult owns the keys to the child’s mind and the child may not even know what he or she is missing. With teaching, the children own the keys to their own minds and are treated as independent thinkers who may reach different conclusions than the teacher.

Despite that old man’s treatment of the subject, indoctrination isn’t funny—it’s harmful and abusive. I can’t speak for others, but indoctrination drove me to feel guilty when I shouldn’t and it made me feel as if I had to hide my identity from those I was “closest” with.

Reflecting on all of this makes me wonder which of my other behaviors are a result of my upbringing. How else have I been conditioned to act and feel? And, how can I put my mind back in the driver’s seat?

More posts in the My Religious Deconstruction series:

How a Christian Teacher Accidentally Shook My Faith (upcoming)

The documentary Shiny Happy People: Duggar Family Secrets documents informational control and many other horrendous things that occur within Christian Fundamentalism.

This isn’t to say that specific Christian friends of mine morally condemn me and others for listening to such kinds of music. My goal isn’t to stereotype. I have many Christian friends today who are very open to new experiences and don’t attempt to guilt me for the choices I make—but, in my opinion, these kinds of Christians represent a break from Christian ideas, not an adherence to them. Many Christians in my past really did tell me that certain kinds of music, media, and so on are sinful or this worldly, which is what indoctrinated me and is part of what produced my visceral reaction to Unholy playing.

This is really making me pause and consider what in my life could be indoctrination vs my own choice. I also wonder where the line between teaching and indoctrination really is. I think even teachers who do present all the facts can have biases and shame kids to lean one way.

I'm glad you made it out with your reason intact!